How Banks Can Lead the Shift to AI-First

Banking provides a fertile ground for artificial intelligence. After all, AI lives on data, and banks are information businesses with terabytes of data. One breakthrough in AI is supervised learning, which enables a machine to mimic a human’s decision-making process based on what may be millions of examples. This advance has made switching to an AI-first business model a natural progression for banks, which are leading the charge in digital and mobile-first strategies.

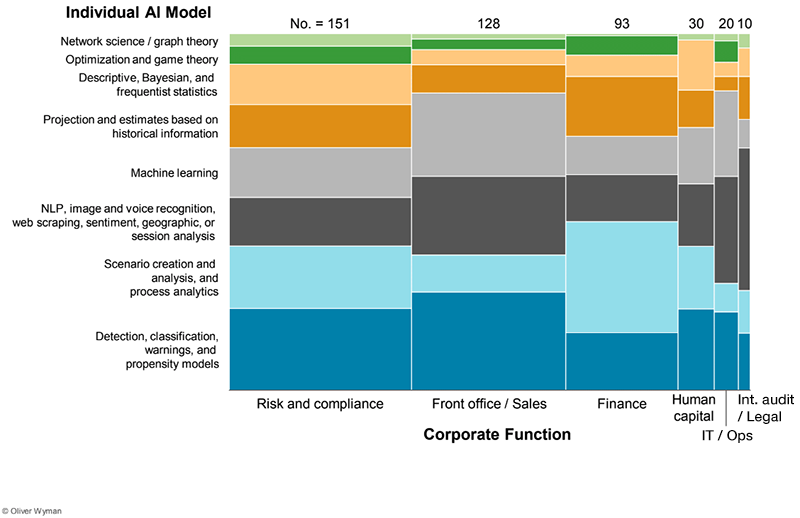

If properly deployed in the next five to seven years, we estimate that AI could increase banks’ revenues by as much as 30% and potentially reduce their costs by 25% or more. To date, however, most banks have been scattershot in their approach to deploying AI, with models ranging from customer-support chatbots to price-elasticity analytics. But rolling out one model at a time, à la carte, without an overriding strategy, is certainly a recipe for failure given the hundreds of possible use cases AI now provides. (See “AI-First Bank Use Cases.”)

Banks need a clear AI strategy to get this transformation right. If they don’t have one, other banks that master AI will offer their customers more tailored services with lower fees. The template we’ve found working with global financial services companies to develop AI-first business models — and avoid being trapped in a revolving door of AI initiatives that are ultimately ineffective — can work for organizations in other industries as well. The most successful AI strategies are driven by four pillars: improving data assets, scaling infrastructure to allow widespread experimentation, enlisting employees so that they scout for new AI use cases, and looking for ways AI can solve customers’ problems beyond providing banking services.

A structural approach is needed to handle the hundreds of possible use cases AI now provides.

Below are the four key components of a successful AI strategy, with examples of how leading companies have shifted to an AI-first paradigm:

1. Improve Data AssetsMost AI models for banking are relatively easy to build, copy, or buy. What makes them valuable is data when it is easy to access, load, and prepare for AI algorithms. Right now, banks have serious problems organizing their data. It is scattered across systems, making it cumbersome to retrieve. Customer interactions within branches are only partially logged, for example, even though these conversations are some of most valuable assets a bank has. Imagine how much richer customer profiles would be if you knew the thought process that preceded a product purchase.

A bank needs to develop a systematic way to build up its data assets, using instant access to internal and external sources, with both historic and real-time data. At the same time, a bank needs to subtly balance proactive collation of different data sets versus a reactive search for data when the business seeks to deploy a specific AI application. The objective should be to capture and stockpile data that is relevant to models you have or want to build.

For instance, American Express is harnessing the power of its data, derived from over 100 million credit cards that account for over $1 trillion in charges every year, by migrating many of its traditional processes from legacy mainframes to big-data databases. Using machine learning algorithms, Amex can now use data on cardholder spending across more than 100 variables to provide customized offers to attract and retain customers. Amex also leverages this information to match merchants with customers who are likely to spend more and be loyal.

2. Deploy AI at ScaleTo be effective, an AI-first bank needs to deploy AI models at scale. That means facing the possibility of thousands of models running at any moment, some serving millions of customers or reviewing millions of transactions per day. Many of these models will be recalibrated monthly, some even daily.

Deploying one AI model is not particularly difficult, but applying it to a million people is a challenge due to the unpredictable nature of client contexts. And managing multiple models, even hundreds of models, raises the degree of difficulty several more notches.

Part of the problem is that AI is like alchemy: We don’t fully understand why it works and when it might break down. In assessing creditworthiness, for example, a model that has not been well-tested might jump to conclusions about people based on a few pieces of data, such as home address or education level.

Banks need to develop their infrastructure with one clear deployment platform across the organization and a method for managing models. JPMorgan Chase, for example, last year budgeted $10.8 billion for technology investments, with more than $5 billion earmarked for new investments. These investments have enabled several AI initiatives at scale, including routine automation that can process 12,000 credit agreements in seconds — which used to take 360,000 person-hours of manual review; customer-transaction analysis to support follow-up trading; and a chatbot that will free up people for higher-level tasks while providing top-notch customer support 24/7.

3. Ingrain AI in the Organizational CultureIt is important that employees see AI as an opportunity, not as a threat to their job security. AI can be applied widely to both support people and fully automate processes. To identify potential opportunities, employees need to scout for them. By using robots to perform rote, repetitive tasks, organizations will be able to open up pathways for new business models that serve clients better while freeing the employees’ time for higher-level work.

Allstate Business Insurance Expert’s web-based chatbot ABIE, for example, helps agents quote and issue Allstate Business Insurance products without engaging a call center, enabling them to sell more insurance. ABIE answers questions and finds critical documents. It understands the agents’ context — who they are, what product they’re working on, and where they are in the process.

Similarly, HSBC is working with Ayasdi, a Silicon Valley AI startup, to automate money-laundering investigations that have traditionally been conducted by people. HSBC creates a decision tree to show how decisions are made, aiming to bypass the “black box” rap against machine learning, which cannot be allowed in the tightly regulated finance sector. HSBC claims to have unearthed many new patterns directly correlated to fraud — as well as reducing HSBC’s false alerts by 20%.

4. Extend AI Services Beyond BankingThe boundaries between banking, financial advice, and other advisory services are blurring. AI will only accelerate this trend. This presents an opportunity for banks to become trusted financial advisers on a range of issues, from car purchases to health advice. Many other businesses have showed that if you focus on customer problems, the profits will follow.

Ping An, a Chinese AI-first, financial-services provider, has implemented a Good Doctor AI service. It allows for remote diagnosis of a health concern, using a chatbot to understand a patient’s situation, provide initial diagnosis, and direct the patient to the most suitable doctor. The platform manages 300,000 to 400,000 daily consultations, with roughly 1,000 medical professionals providing continuous feedback.

This bold extension beyond financial services into health care, not typically considered an adjacent space, highlights the potential for AI to widen the playing field — and the need for banks, already competing with fintechs in the finance space, to make the AI transformation and stave off further business erosion.

Move Along the AI ContinuumAI is now a natural fit for banks and will increasingly be suitable for other companies as all industries become progressively more digital. As we’re already seeing in financial services, if properly applied, AI can drive down costs and improve customer experience. But to get these benefits, AI must be deployed at scale in a differentiated way.

Companies both inside and outside of financial services need to adopt a clear AI-first strategy. Otherwise, they risk creating a web of interconnected models, with many analogs to the troublesome, patchwork IT architecture of the past.

Once companies have a clear AI strategy and management plan, they can build relatively simple models that provide a short-term impact. The financial benefits of these short-term models can then pay for build-out of the platform needed for more sophisticated models further down the line.

Given the benefits in terms of cost savings and new customer acquisitions, the potential of AI is too large to ignore. So is the threat from startups who are moving along the AI continuum, looking to lure customers away from less agile competitors. The time to think in terms of AI-first business models is now.

Barbara Chase/Getty Images

Barbara Chase/Getty Images Some of the worst corporate disasters of the past two decades were heralded by whistleblowers: Sherron Watkins raised the red flag internally at Enron, Cynthia Cooper let management know of major accounting problems at WorldCom, and Matthew Lee brought problems to his management team at Lehman Brothers. The whistleblowers weren’t able to halt their companies’ declines and—in some cases—faced punishment for calling attention to internal misdeeds. Looking at these examples, it would be easy to say that whistleblowers have little impact on how companies both conduct themselves and weather corporate storms. But that’s not the case.

In 2018, NAVEX Global, the leading provider of whistleblower hotline and incident management systems, provided us secure, anonymized access to more than 1.2 million records of internal reports made by employees of public U.S. companies. Our analysis revealed that whistleblowers—and large numbers of them—are crucial to keeping firms healthy and that functioning internal hotlines are of paramount importance to business goals including profitability. The more employees use internal whistleblowing hotlines, the less lawsuits companies face, and the less money firms pay out in settlements.

Our conclusions are in many ways counterintuitive to how many executives manage complaints. Many companies continue to ignore—or misuse—whistleblower hotlines, and most don’t know what make of the information that is provided through them. Even when firms want to support whistleblowers, managers don’t know what to make of reported level of internal reports. Are more internal reports of problems a signal of widespread troubles within the firm? Research on external whistleblowing events, by Robert Bowen, Andrew Call, and Shiva Rajgopal finds that more external reporting events is associated with increased future lawsuits and negative performance. Does this finding on external reporting hold true for internal reporting events? Or do more reports instead reflect employees’ trust in management and a communication channel that allows management to more effectively prevent public disasters before they occur?

More whistles blown are a sign of health, not illnessWe found that firms actively using their internal reporting systems face fewer material lawsuits and have lower settlement amounts than firms ignoring—or minimally using—similar information. While all firms are likely to have some frequency of issues, firms where these are reported early are more likely to address them before they become larger problems resulting in costly litigation.

We measured activity from the perspectives of employees and managers, assessing both the number of internal reports filed and the amount of information provided in each report. We also measured the number of times reports were accessed and reviewed by management. We found that a one standard deviation increase in the use of an internal reporting system is associated with 6.9% fewer pending lawsuits and 20.4% less in aggregate settlement amounts.

We also found that higher use of internal reporting systems is not associated with a greater volume of external reports to regulatory agencies or other authorities. This suggests that a higher volume of internal reports does not imply that problems at the company are more frequent or severe. Instead, internal reports indicate open communication channels between employees and management and a belief that issues raised will be addressed. At the same time, when employees do report externally, it reflects management’s failure to address issues internally.

Types of firms that actively use internal whistleblower hotlinesWhile the use of internal reporting systems, proxied by the number of reports filed, has increased over time, how those systems are used varies substantially across firms and industries.

What types of companies are actively using internal reporting systems? We saw a few common characteristics in our research. Using an index developed by Lucian Bebchuk, Alma Cohen, and Allen Ferrell in 2009, we found that firms with more powerful management—e.g., firms with governance protocols that limit shareholder power relative to firm leadership—are less likely to actively use their internal reporting systems. Fast-growing companies are also less likely to use their internal reporting systems, as are firms that show signs of potential earnings misstatements. Firms that are more active in using their systems tend to be more profitable (as measured by return on assets) than firms that are less active users of their systems.

We found that companies that more actively use their internal reporting systems can identify and address problems internally before litigation becomes likely. Significantly, our analysis shows that a one-standard-deviation increase in the use of an internal reporting system is associated with 3.9% fewer pending material lawsuits in the subsequent year and 8.9% lower aggregate legal settlement amounts. Over a three-year period, a one standard deviation increase was associated with 6.9% fewer lawsuits and 20.4% lower settlement amounts. Avoiding lawsuits is important for reasons beyond just the direct financial costs of legal defense and settlements. Although settlement costs can often be in the hundreds of millions of dollars, the hit to brand reputation and stock price can easily exceed all other out-of-pocket expenses. We found that in addition to reduced legal exposure, firms that more actively use their internal reporting systems are typically more profitable and have been in business longer.

What this meansIn our discussions with compliance officers at firms, many executive leadership teams stated a “goal” to have zero reports. This is not hard to accomplish if you simply don’t make your employees aware of the system or comfortable using it. There is evidence that this is often the case: In 2014, Bruckhaus Deringer found that nearly 30% of managers in their survey reported that their company actively discourages whistleblowing.

Other executives seem to understand that having few or no reports signals a poorly used system, but they also seem to think that going beyond the industry average number reports is a sign that the firm has more problems than they should.

Our research provides strong evidence that neither of these assertions are true: high usage is more often a sign of a healthy culture of open communication between employees and management than a harbinger of real trouble. After all, all large organizations face a large amount of common, unavoidable, and unobserved problems. Internal reporting systems simply make those problems visible to management.

Managers should view hotlines as a critical component of traditional audit mechanisms and board of director meetings. The reports seem to be a valuable resource to identify and quickly address concerns arising within the firm. And regulators are on the hook, too. Given what we learned about how companies with strong internal reporting systems fair, regulators might rethink the recent prioritization of external over internal whistleblowing and provide greater incentives for companies to implement their own effective solutions.

Mark Edward Harris/Getty Images

Mark Edward Harris/Getty Images What working parent hasn’t felt guilty about missing soccer games and piano recitals? When there are last-minute schedule changes at work or required travel to a client site, it’s normal to worry that you’re somehow permanently scarring your little one.

But how does our work affect our children’s lives? About two decades ago, in a study that surveyed approximately 900 business professionals ranging from 25 to 63 years old, across an array of industries, Drexel University’s Jeff Greenhaus and I explored the relationship between work and family life and described how these two aspects of life are both allies and enemies. In light of the deservedly increased attention we’re now paying to mental health problems in our society, it’s worth taking a fresh look at some of our findings on how the emotional lives of children — the unseen stakeholders at work — are affected by their parents’ careers. Our findings help explain what’s been observed since our original research about how children are negatively affected by their parents being digitally distracted, also known as “technoference,” and by the harmful effects of stress at work on family life.

Most of the research on the impact of parental employment on children looks at whether or not mothers work (but not, until very recently, fathers); whether parents work full- or part-time; the amount of time parents spend at work; and the timing of parental employment in the span of children’s lives. Our research went beyond matters of time, however, and looked, in addition, at the inner experience of work: parental values about the importance of career and family, the psychological interference of work on family life (that is, we are thinking about work when we are physically present at home with our family), the extent of emotional involvement in career, and discretion and control about the conditions of work.

All these aspects of parents’ careers, we found, correlate with the degree to which children display behavior problems, which are key indicators of their mental health. We measured them with the Child Behavior Checklist, a standard in the child development research literature that has not been used in other research in organizational psychology. Unfortunately, to date, the specific effects of parents’ work experiences (not time spent at work) on children’s mental health has still not been a priority for research in this field. It should be, for this is yet another means by which work can have important health consequences. Here are some of the highlights of what we observed.

For both mothers and fathers, we found that children’s emotional health was higher when parents believed that family should come first, regardless of the amount of time they spent working. We also found children were better off when parents cared about work as a source of challenge, creativity, and enjoyment, again, without regard to the time spent. And, not surprisingly, we saw that children were better off when parents were able to be physically available to them.

Children were more likely to show behavioral problems if their fathers were overly involved psychologically in their careers, whether or not they worked long hours. And a father’s cognitive interference of work on family and relaxation time — that is, a father’s psychological availability, or presence, which is noticeably absent when he is on his digital device — was also linked with children having emotional and behavioral problems. On the other hand, to the extent that a father was performing well in and feeling satisfied with his job, his children were likely to demonstrate relatively few behavior problems, again, independent of how long he was working.

For mothers, on the other hand, having authority and discretion at work was associated with mentally healthier children. That is, we found that children benefit if their mothers have control over what happens to them when they are working. Further, mothers spending time on themselves — on relaxation and self-care — and not so much on housework, was associated with positive outcomes for children. It’s not just a matter of mothers being at home versus at work, it’s what they do when they’re at home with their non-work time. If mothers were not with their children so they could take care of themselves, there was no ill effect on their children. But to the extent that mothers were engaged in housework, children were more likely to be beset by behavior problems.

Traditional roles for fathers and mothers are surely changing since we conducted this research. But it’s still the case that women carry more of the psychological burden of parental responsibilities. Our research showed that taking time to care for themselves instead of on the additional labor of housework strengthens mothers’ capacities to care their children. And fathers are better able to provide healthy experiences for their children when they are psychologically present with them and when their sense of competence and their well-being are enhanced by their work.

The good news in this research is that these features of a parent’s working life are, at least to some degree, under their control and can be changed. We were surprised to see in our study that parents’ time spent working and on child care — variables often much harder to do anything about, in light of economic and industry conditions — did not influence children’s mental health. So, if we care about how our careers are affecting our children’s mental health, we can and should focus on the value we place on our careers and experiment with creative ways to be available, physically and psychologically, to our children, though not necessarily in more hours with them. Quality time is real.

https://www.tampabusinessconsulting.com/2018/11/how-banks-can-lead-shift-to-ai-first.html